|

Federalism, the Key to Irish Reunification

One

would expect that anyone with a basic knowledge of government

structures if asked the question,

'What would be the best form of government for a reunited Ireland?',

their

answer would

be,

Ďa unitary systemí. More than likely their reasoning would be

based on its landmass, population size, and the homogeneity of its

inhabitants. One

would expect that anyone with a basic knowledge of government

structures if asked the question,

'What would be the best form of government for a reunited Ireland?',

their

answer would

be,

Ďa unitary systemí. More than likely their reasoning would be

based on its landmass, population size, and the homogeneity of its

inhabitants.

Under

normal circumstances that answer, Ďa unitary systemí, would

be correct without equivocation. However, circumstances surrounding

the homogeneity of Ireland's people are not as normal or clear cut

as they might seem. Since Ireland was partitioned into two states

by the British over a hundred years ago, the dividing line drawn

between the two states has been a godsend for religious zealots and

political demagogues, more so in the Northern Ireland state. As

a result, the harm caused to peaceful coexistence has been profound

and reprehensible and has rendered homogeneity a myth in the

Northern state.

Religious identity rather than religious ethos was what mattered in

the Northern state. It was the criteria used to determine where you

lived, who your friends were, where you went to school, where you

worked --- it was your lifeís determinant, it was the zealotís

witchcraft. The sound of the Lambeg drum every July 12th for

centuries is the manifestation of that perversion. That state of

affairs prevailed through the 1970s. Due to a 30-year low-grade war

and the advent of the European Unionís influence on human rights,

labor law and investment within the state, as well as evolutionary

societal changes, the situation has improved somewhat, but less so

the mind-set.

In what

became the Free State in 1922, religious identity played a much

different role where Catholics accounted for ninety percent of the

population, and Protestants accounted for the other ten percent.

After 1922, as many as 40,000 Protestants left the Free State, some

out of fear for the unknown, others who felt they no longer belonged

and others still who supported the British occupation and genuinely

feared for their lives. By 2011, the Protestant population had

dwindled to less than five percent.

From the

inception of the Free State, its leaders forged an unholy alliance

with the Catholic Hierarchy to help keep the people in check after a

bitter civil war and to mollify them during periods of dour economic

downturns. For the subsequent six decades, that unholy alliance

shielded the existence of atrocious and deviant behavior within

state institutions operated and staffed by members of Catholic

religious orders. When the scandals came to light in the latter

quarter of the twentieth century, the Catholic Churchís influence

drastically declined to the point where itís no longer a relevant

force in Irish life. The many good men and women who dedicated

their lives to the church were also victims of their

ecclesiastical superiors who were either

participants or silent facilitators to the goings-on.

The

existing unitary system of government in Ireland operates more like

the government of a city-state than the government of a state that

includes cities, towns, villages and significant rural areas. One

may argue that such an inference is off the mark, pointing to

Ireland as a modern society with a high standard of living

comparable to other European countries. Conceding that point, the

fact remains that the governmentís focus and policies are Dublin

centric in that everything emanates outwards from there. Dublin and

its environs enjoy first dibs or the lionís share of every major

project or investment controlled or touched by the government in

Dublin.

The

totality of the situation in both states in Ireland is complex,

entrenched and difficult to navigate. Itís not only the political

and geographical aspects of reunification that require solutions,

but other issues including rural development, access to government

services, the disparity in the distribution of wealth and the

systemic corruption at all government levels. A peaceful and

prosperous reunited Ireland depends on a more equitable society

where everyone is a valued citizen and treated fairly. That should

be the basis for a reunited Ireland.

Although

the top-down unitary system has many advantages, it has not

functioned as well as it should have in Ireland for the reasons

stated in this article. It would prove even less effective as a

framework for a reunited Ireland. Itís also a fact that the powers

that be in Northern Ireland would be reluctant to set aside their

own on again, off again dysfunctional government to be absorbed into

what they consider to be an inept and insular Dublin government.

To avoid such problems, the

Eire Athaonthaithe proposal envisions an all-Ireland

Federal Parliamentary Republic comprised of three distinct regions

namely, 1) the

Ulster Region

encompassing the nine counties of Ulster, 2) the Munster/Connacht

Region encompassing the eleven counties of Munster and Connacht, and

3) the Leinster Region encompassing the twelve counties of

Leinster.

The

union of Connacht and Munster into a single region would

lend economic equity and political balance to what would be

lacking in a standalone Connacht and to a lesser extent, in

a standalone Munster.

The proposed federation would be underpinned by a new constitution that

would provide for the allotment of governmental powers between a

national and regional governments

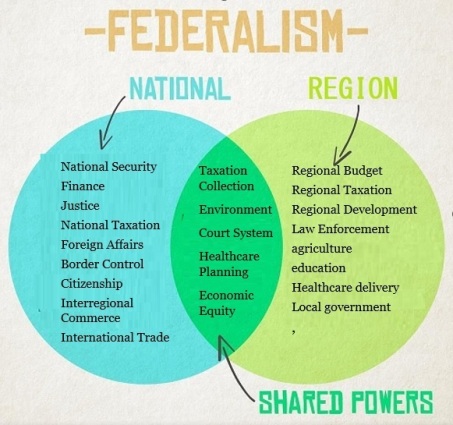

To that

end, government powers

reserved for the national government would be those that blanket the

nation as a whole to protect its people, security, independence and

territorial integrity as well as effectively represent the nation on

the world stage. By the same token, government powers reserved for regional governments would be those best exercised at

the regional level where the outcome would directly affect the

people of the region.

Shared

powers would be handled by inter-government regulatory agencies and

shared oversight responsibilities by inter-government commissions.

The new constitution would be the nationís supreme authority that all

government entities and the people at large would bear true faith and allegiance to.

Holistically, Eire

Athaontaithe provides the framework for political and

cultural differences to coexist in harmony and exercised in

conformity with universally accepted democratic principles.

Contributed by TMMTP

|